|

|

|

||

|

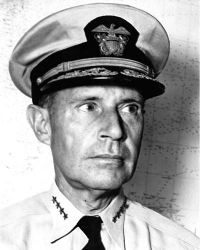

Raymond Ames Spruance |

||||

|

Graduate, U.S. Naval Academy, Class of 1906 Engagements: • World War I (1914 - 1918)• World War II (1941 - 1945) |

||||

| Biography: | ||||

|

Raymond Ames Spruance Raymond Ames Spruance was born on 3 July 1886 in Baltimore, MD, to Alexander and Annie Spruance. He was raised in Indianapolis, IN. Spruance attended Indianapolis public schools and graduated from Shortridge High School. He graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1906. During the early part of his Naval career, he received further practical education in electrical engineering. His service at sea included command of the USS Osborne, four other destroyers, and the battleship USS Mississippi (BB-41). Prior to the 1940s, Spruance also held several engineering, intelligence, staff, and Naval War College positions. In 1940-41, he commanded the 10th Naval District and Caribbean Sea Frontier, headquartered at San Juan, Puerto Rico. World War II Before Midway In the first months of World War II in the Pacific, Spruance commanded four heavy cruisers and support ships that made up Cruiser Division Five. Spruance's division was under a task force built around the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise commanded by Admiral William "Bull" Halsey. Halsey led a series of hit and run raids against the Japanese, striking the Gilbert and Marshall islands in February, Wake Island in March, and carrying out the Doolittle Raid in April against targets on the Japanese homeland. The raids were important to morale, setting a tone of aggressive initiative taking, and also provided invaluable experience for the U.S. Navy. Battle of Midway Admiral Halsey, commander of the Pacific aircraft carrier force, came down with a severe case of psoriasis just before the battle, which hospitalized him. He recommended Spruance to Pacific Fleet Commander Chester W. Nimitz to take his place. Spruance had up to that time been a Cruiser Division Commander, and there was some concern that he had no experience in handling a carrier, or air battle. Halsey reassured him, telling Spruance to rely on his able staff, particularly Captain Miles Browning, a battle-proven expert in carrier warfare. Spruance commanded Task Force 16, with two aircraft carriers, USS Enterprise (flagship) and USS Hornet, and was under the overall command of Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, who was trailing behind in the damaged USS Yorktown. The U.S. task force, based on three carriers, faced a Japanese force with four fleet carriers, divided into two groups; a lead group under Admiral Nagumo and a follow-on group under Admiral Yamamoto. The U.S. Navy lost one carrier while sinking all four of the enemy's fleet carriers. The U.S. victory came largely from the toughness of the fighting force; Spruance's combination of coolness plus his caution at just the right moments; and large doses of plain luck. Several waves of U.S. aircraft were beaten badly by the Japanese both at the Island of Midway and at sea around the Japanese task force. Then a large group of U.S. dive bombers happened to find Nagamo's four carriers-with their air cover absent. The Japanese planes had all been sent to attack the American ships. The U.S. dive bombers badly damaged the Japanese carriers, all of them eventually sinking, which essentially ended the Japanese lead in fleet power in the Pacific. Historian Samuel E. Morison wrote in 1949 that Spruance was subjected to much criticism for not pursuing the retreating Japanese, and allowing the retreating Japanese surface fleet to escape. However, Spruance was recommended for the Navy Distinguished Service Medal by both Fletcher and Nimitz for his role in the battle. Before Midway, a small and fractional U.S. Navy in the Pacific faced an overwhelmingly large and battle-hardened Japanese fleet. After Midway, the Japanese still held a temporary advantage in vessels and planes, but the setback gave the slow-to-crank-up U.S. industrial production time to turn the tables. It also gave the U.S. Navy confidence. Once running at full speed, American factories handed the allies a huge advantage against not only the Japanese, but also the Germans. At the same time, American Pacific forces before and after Midway gained crucial combat experience; so the Japanese lost the advantage there as well. Truk, Philippine Sea and Iwo Jima After the Battle of Midway, Spruance became Chief of Staff to the Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet (CINCPAC) and later was Deputy Commander-in-Chief. In mid-1943, Spruance was given command of the Central Pacific Force. The command of the vessels which made up the big blue fleet alternated between Admiral William Halsey, at which time it was identified as the Third Fleet and Task Force 38, and Admiral Spruance, in which it became the Fifth Fleet and Task Force 58. The two Admirals were a contrast in styles: Halsey was aggressive and a risk taker; Spruance was professional, calculating and cautious. Most common sailors were proud to serve under Halsey; most higher-ranking officers preferred to serve under Spruance. Captain George Dyer of the CL Astoria, who served under both Spruance and Halsey, summed up the view of many ship captains: "My feeling was one of confidence when Spruance was there. When you moved into Admiral Halsey's command from Admiral Spruance's ... you moved from an area in which you never knew what you were going to do in the next five minutes or how you were going to do it, because the printed instructions were never up to date.... He never did things the same way twice. When you moved into Admiral Spruance's command, the printed instructions were up to date, and you did things in accordance with them." From 1943-45, with USS Indianapolis or the USS New Jersey as his flagship, Spruance directed the campaigns that captured the Gilbert Islands, Marshall Islands, Marianas, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. On 16 February 1944, Spruance was promoted to the four-star rank of Admiral. He also directed Operation Hailstone against the Japanese naval base Truk in February 1944 in which twelve Japanese warships, thirty-two merchant ships and 249 aircraft were destroyed. While screening the American invasion of Saipan in June 1944, Spruance also defeated the Japanese fleet in the Battle of the Philippine Sea. He broke the back of the Japanese naval air force by sinking 3 carriers, 2 oilers and destroying about 600 enemy airplanes. The Japanese losses were so great that in the Battle of Leyte Gulf a few months later the remaining Japanese carriers were used solely as decoys against Admiral Halsey due to the lack of aircraft, and aircrews to fly them. Still, Spruance was criticized for not being aggressive enough in exploiting his success in the Philippine Sea. Buell quotes Spruance speaking with Morison: "As a matter of tactics I think that going out after the Japanese and knocking their carriers out would have been much better and more satisfactory than waiting for them to attack us, but we were at the start of a very important and large amphibious operation and we could not afford to gamble and place it in jeopardy." Just as at Midway, Spruance could be counted on to "stay on station." However, Spruance's actions were both praised or understood by the main persons ordering and directly involved in the battle. Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King told him "Spruance, you did a damn fine job there. No matter what other people tell you, your decision was correct." Spruance's fast carrier commander, Marc Mitscher, told his chief of staff Arleigh Burke that: "You and I have been in many battles, and we know there are always some mistakes. This time we were right because the enemy did what we expected him to do. Admiral Spruance could have been right. He's one of the finest officers I know of. It was his job to protect the landing force...." He succeeded Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz as Commander-in-Chief, US Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas in November 1945. Spruance's promotion to Fleet Admiral was blocked multiple times by Congressman Carl Vinson, a staunch partisan of Admiral William Halsey. Congress eventually responded by passing an unprecedented act that specified that once Spruance was retired, he would remain on full Admiral's pay until death. He was President of the Naval War College from February 1946 until he retired from the Navy in July 1948. In Retirement Spruance was appointed as American Ambassador to the Philippines by President Harry Truman, and served there from 1952 to 1955. Honors The destroyers USS Spruance (DD-963), lead ship of the Spruance-class of destroyers, and USS Spruance (DDG-111), 61st ship of the Arleigh Burke-class destroyer, were named in his honor. Death and Burial Admiral Raymond Ames Spruance died on 13 December 1969 in Pebble Beach, CA. He is buried at Golden Gate National Cemetery in San Bruno, CA, alongside his wife, Margaret Dean. Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz; his longtime friend; Admiral Richmond K. Turner; and Admiral Charles A. Lockwood had arranged for burial there. |

||||

| Honoree ID: 653 | Created by: MHOH | |||

Ribbons

Medals

Badges

Honoree Photos

|  |  |

|  |

|