|

|

|

||

|

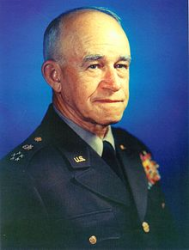

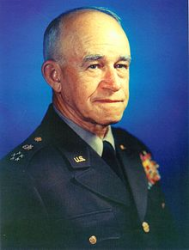

Omar Nelson Bradley |

||||

|

Graduate, U.S. Military Academy, Class of 1915 Engagements: • World War II (1941 - 1945)• Korean War (1950 - 1953) |

||||

| Biography: | ||||

|

Biography Early Years Omar Nelson Bradley was born in a log cabin on the Hubbard farm near Clark, in Randolph County, MO, on 12 February 1893. He was the first born and only surviving child (a brother, Raymond Calvert, was born in February 1900 and died 18 January 1902) of schoolteacher John Smith and Sarah Elizabeth (nee Hubbard) Bradley. Although the rural Missouri area where Bradley grew up was poor, he received a good grade school education attending country schools where his father taught. Bradley's father, whom he credited with teaching him a love for books, playing baseball, and shooting, died 12 days before his fifteenth birthday. A short time later, his mother moved to Moberly and remarried. Bradley, an outstanding student and captain of both the baseball and football teams, graduated from Moberly High School in 1910. After graduating from high school, Bradley went to work as a boiler maker for the Wabash Railroad in order to earn enough money to enter the University of Missouri and study law. But Bradley's plans changed when his Sunday school teacher at Central Christian Church in Moberly encouraged him to take the entrance examination for the U.S. Military Academy. He finished second in the West Point placement exams held at Jefferson Barracks Military Post in St. Louis. However, the first place winner was unable to accept the Congressional appointment, deferring instead to Bradley. Thus it came about that Bradley received an appointment from Congressman William M. Rucker to enter the USMA in the fall of 1911. Some cadets had difficulty adapting to the demanding curriculum and strict military life at West Point. But Brad (a nickname he was given at West Point and used for the rest of his life) said that the discipline, the rigors of a code of conduct centering on honor and duty, the structured society, and the opportunities for athletics, greatly appealed to him. At the Academy, Brad's focus on sports prevented him from excelling academically but he still managed to finish a respectable 44th in his graduating class of 164. He was a baseball star and often played on semi-pro teams for no remuneration (to ensure his eligibility to represent the Academy). He was considered one of the most outstanding college players in the nation during his junior and senior seasons at West Point, noted as both a power hitter and an outfielder with one of the best arms in his day. He lettered both in football and baseball (3 letters) and he later commented on the importance of sports in teaching the art of group cooperation. Like his classmate Dwight D. Eisenhower, Brad was not particularly distinguished in the purely military side of his cadet years, achieving the rank of cadet lieutenant only in his final year. But cadet rank turned out to have little to do with future achievement for the class of 1915, which came to be known as "the class the stars fell on" because so many of its members became generals. Eventually, 59 generals came from that graduating class, with Dwight Eisenhower and Bradley both attaining the rank of General of the Army. Some of his classmates would end up commanding Bradley's divisions and corps during World War II. Brad graduated from West Point on 12 June 1915, and was commissioned a second lieutenant of Infantry. Three months later he joined the 14th Infantry Regiment's Third Battalion at Fort George Wright, near Spokane, WA, where he was exposed to the old Regular Army life that would shortly disappear forever. Under the tutorship of Second Lieutenant Edwin Forrest Harding, who was six years his senior, Brad began a lifelong practice of studying his profession. Harding was a natural schoolmaster who led a small group of lieutenants through weekly tactical exercises that broadened into discussions of military history and current operations in Europe. Few people had a greater influence on Brad than Harding, who convinced him that an officer had to begin studying at the very start of his career and continue to study regularly if he hoped to master his profession. Lieutenant Bradley's developing military skills were put to a first, rather modest, test when the civil war in Mexico spilled over the border into the United States. Brigadier General John J. Pershing, commanding American regulars, marched into Mexico in pursuit of the rebel commander, Pancho Villa. Due to the likelihood of an actual war with Mexico, the War Department called up National Guard units from Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico and ordered more Regular Army units to the border. Among them was the 14th Infantry, which went into camp at Douglas, AZ. Although Brad saw no action on the Mexican border, he learned about handling troops in field conditions; conducting long motor marches; and maintaining discipline, morale, and training in unfavorable circumstances. In the midst of the crisis, Congress passed the National Defense Act of 1916, doubling the authorized size of the Regular Army and increasing the number of infantry regiments to sixty-five. As a result of the expansion, Brad was promoted to first lieutenant only seventeen months after graduating from West Point. Although the crisis with Mexico passed, Brad and his regiment stayed in the Southwest until after the U. S. declared war on the German Empire. World War I and the Interwar Years The 14th Infantry was stationed at Yuma, AZ, when the U. S. formally entered World War I. As the Army began to mobilize, Brad was almost immediately promoted to captain. But instead of moving to Europe, his regiment received orders to go to the Pacific Northwest, where it would police the copper mines in Butte, MT. Brad spent the next year desperately trying to get assigned to a unit bound for the fighting in France, but to no avail. Shortly after Brad was promoted to major in August 1918, he received the highly-desired orders to prepare for duty overseas. The 14th Infantry, with Bradley in command of its Second Battalion, became part of the new 19th Infantry Division that was organizing at Camp Dodge, near Des Moines, IA. But the great influenza epidemic of 1918, coupled with the armistice in November, ensured that the division would never go overseas. With the war over, the Army rapidly demobilized and a frustrated Bradley never saw the battlefields of the Western Front. He was then posted to South Dakota State College, where he spent a year as an Assistant Professor of Military Science, and was reduced to his permanent grade of captain. In September 1920, Brad began a four-year tour of duty as an instructor of mathematics at West Point; Douglas MacArthur was superintendent at the time. Aside from the rigor of studying mathematics, he devoted his time at the Academy to the study of military history. He was especially interested in the campaigns of General William T. Sherman, whom he considered a master of the war of movement. In the spring of 1924, Brad was again promoted to major. By the time he was ordered to attend the advanced course at the Infantry School at Fort Benning, GA, that fall, he had concluded that many of the men who had fought in France had been misled by the experience of that static war. Brad felt that Sherman's campaigns were more relevant to any future war than the battle reports from the American Expeditionary Forces. Since the curriculum at the Infantry School stressed open warfare, Brad had the chance to become a specialist in tactics and terrain, and in the problems of fire and movement. He graduated second in his class (behind Leonard T. Gerow, another officer with whom he was to serve years later) and ahead of officers who had combat experience in World War I. It was at Fort Benning that Brad concluded that his tactical judgment was equal to that of men tested in battle. His Infantry School experience was crucial. As he later explained, "the confidence I needed had been restored; I never suffered a faint heart again." After his Fort Benning tour ended, Brad was assigned to the 27th Infantry of the Hawaiian Division. There he met George S. Patton, Jr., the division G-2, whose future would be intertwined with his for many years. Following a stint with the Hawaiian National Guard, Brad returned to the U. S. in 1928 as a student at the Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, KS. The premier school for professional soldiers, Leavenworth was the eye of the needle through which any officer who hoped for high rank in the Army had to pass. Brad was somewhat critical of the instruction he received there. He deemed the old "school solutions" the faculty presented, to be predictable and unimaginative. Still, he judged that his year in Kansas stimulated his thinking about tactical problems and, voicing a conclusion shared by many of his peers, believed the real importance of the Command and General Staff School was that it gave his entire generation of officers a common tactical language and technique for problem solving. Brad's assignment as an instructor at the Infantry School in 1929 was more important to him than Leavenworth had been. George C. Marshall, the assistant commandant, was determined to streamline and simplify tactical command procedures. Under Marshall's guidance, instructors encouraged student officers to think creatively about tactical problems and to simplify doctrine so that it was meaningful for citizen-soldiers; instead of just an Army composed of professionals. Brad felt that Marshall had a more profound influence on him, personally and professionally, than anyone else ever had. Once Marshall gave a man a job, he never intervened if the officer performed as he desired. Impressed with the results of Marshall's methods, Brad adopted an identical hands-off style of command. His four-year assignment at the Infantry School brought another intangible benefit. During this tour, Brad associated with a hand-picked company of "Marshall Men," some of whom (i.e. Forrest Harding) he had known before. Others, both faculty and students, and including such men as Joseph Stilwell, Charles Lanham, W. Bedell Smith, Harold Bull, Matthew Ridgway, and J. Lawton Collins, would hold important assignments in a very few years. Rounding out Brad's tactical education was Marshall's personal teaching (in part through the informal seminars he conducted for his staff) and the thought-provoking company of a group of officers devoted to studying their profession. The fact that Brad had made a positive impression on Marshall would prove crucial to his successful future in the Army. Bradley graduated from the Army War College in 1934 and returned to West Point to serve in the Tactical Department. At the Infantry School he had taught and associated with men who would lead divisions and corps during World War II. At West Point he trained cadets - including William C. Westmoreland, Creighton W. Abrams, Jr., Bruce Palmer Jr., John L. Throckmorton, and Andrew J. Goodpaster, Jr. - who would command battalions in that war and then lead the Army in the 1960s and '70s. Brad was promoted to lieutenant colonel in 1936. When he left West Point in the summer of 1938 for duty on the War Department General Staff, he had spent sixteen years in Army schools as student and teacher. After a brief tour in the Army Staff's Manpower and Personnel Office (G-1), Bradley became Assistant Secretary of the General Staff in the Office of Army Chief of Staff, George C. Marshall. Often inundated by the flood of paper, he and Orlando Ward (later assisted by Bedell Smith) filtered the mass of information directed at Marshall, framing problem areas and recommending solutions. In February 1941, the Army had started expanding in anticipation of war with the Axis Powers. Marshall promoted Bradley from lieutenant colonel to brigadier general (making him the first in his West Point class to be a general officer) - bypassing the rank of colonel - and sent him to command the Infantry School at Fort Benning. At the Infantry School, Brad supported the formation and training of tank forces, especially the new 2d Armored Division then commanded by George S. Patton, Jr. He also promoted the growth and development of the new airborne forces, which would play a critical role in the coming war. His most important contribution to the Army, however, was the development of an officer candidate school (OCS) model that would serve as a prototype for similar schools across the Army. When war came, the OCS system would turn out the thousands of lieutenants needed to lead the platoons of an Army that eventually fielded eighty-nine divisions. The Infantry Officer Candidate School at Fort Benning alone would produce some 45,000 officers. When the U. S. formally entered World War II on 8 December 1941, Bradley, at Marshall's suggestion, was preparing a hand-picked successor to take command at Fort Benning. As the Army prepared for combat, Marshall had bigger challenges in mind for Bradley. World War II Bradley took command of the 82d Infantry Division in February 1942. The unit had compiled a distinguished combat record in WWI, but it had been reactivated with mostly draftees and only a small Regular Army cadre. Brad saw to it that incoming soldiers were welcomed with military bands and, when they were marched directly to their temporary quarters, they found uniforms, equipment, and a hot meal waiting for them. These practices did much to boost the morale of the often bewildered inductees. Disturbed by the poor physical condition of the new soldiers, Bradley instituted a rigorous physical training program to augment a tough military training schedule. He also invited Alvin York, Medal of Honor winner and the most famous alumnus of the division, to visit his troops. Based on York's remark that most of his own combat shooting had been done at very short range, Bradley adjusted the division's marksmanship program to include a combat course in firing at targets only 25-50 meters away. Brad looked forward to taking the 82d Division to Europe or the Pacific but, barely four months later, he received orders from General Marshall to take command of the 28th Infantry Division, a National Guard unit that Marshall believed needed help badly. Bradley turned over the 82d to Matthew Ridgway and went to Camp Livingston, LA, to address the problems of the Keystone Division. Among the first steps he took was the reassignment of junior officers who were over-age and unable to cope with field conditions; roughly 20 percent of all National Guard first lieutenants in 1941 were forty or older. The senior officers who lacked the knowledge or skills for battalion and regimental command were transferred, too. He also reassigned officers and sergeants within the division to eliminate the "home-town" factor peculiar to 1930s National Guard units; a system that hampered proper discipline. But the worst problems of the 28th Division were not of its own making. The division had been repeatedly levied for officers and noncommissioned officers; over 1,600 had gone to OCS or aviation training since the division was mobilized. Brad put a stop to this drain in manpower and obtained new drafts from OCS to replace the losses. He then began a systematic training program that included the intense physical conditioning he had found necessary in the 82d. He also led the division through increasingly complex tactical exercises at the battalion and regimental level, culminating in amphibious assault training on the Florida coast. The experience Brad had gained from Army schools, and from training recruits in World War I, had much to do with his ability to turn the 82d and 28th into well-trained combat divisions. But he also clearly understood that citizen-soldiers were not professionals and that the Army could not treat them as such. He adopted George Marshall's view that doctrine had to be simplified for execution by soldiers and leaders who had no previous military experience. Indeed, his successes in 1942 owed much to an understanding of the discipline and training needs of citizen-soldiers derived from Marshall's guidance at the Infantry School a decade earlier. In February 1943, General Marshall, having previously remarked that Bradley had been requested for corps command five or six times, ordered him to Austin, TX, to take over X Corps. However, before Bradley could assume that command the orders were countermanded and he found himself enroute to North Africa to work for his classmate Dwight D. Eisenhower. He had occasionally seen Eisenhower but had not served with him since leaving West Point. Brad arrived in North Africa in the aftermath of the Kasserine Pass debacle. He found a much-chastened Eisenhower worrying about the failure of American units to perform well against their more experienced German opponents. The local British commander had been especially harsh in assessing the initial combat performance of the Americans. Bradley's assignment was to serve as Eisenhower's eyes and ears, reporting on the situation on the Tunisian front and the means that might be used to correct the problems that were by then evident to everyone. One of his first important decisions was to advise Eisenhower to relieve Major General Lloyd Fredendall from command of II Corps, whose troops had demonstrated a particularly poor performance at Kasserine. Eisenhower had been reluctant to take such drastic action despite the recommendations of key subordinates, but he finally acted after consulting with Bradley. After Eisenhower assigned George Patton to replace Fredendall, Patton asked Bradley to become his deputy commander. Bradley agreed as long as Patton understood that he still represented Eisenhower, too. On 15 April, Bradley took command of II Corps when Patton left to resume his previously-interrupted planning for landings on Sicily. Although Patton had restored discipline and confidence to II Corps, it still lacked the prowess of British units. Brad's task throughout the remainder of the North African campaign was to convince both his men and the British that the American soldier was as good as any and, that American leaders were as tactically adept as their Allied and Axis counterparts. During the final battles of April and May 1943, Brad achieved his goal. The II Corps attacked northward toward Bizerte, Tunisia avoiding obvious routes of approach and using infantry to attack German defenders on the high ground before bringing up the armor. The 34th Infantry Division, maligned by the British as a unit with poor fighting qualities, fought the crucial battle and dislodged the Germans from strong defensive positions astride Hill 609, the highest terrain in the corps sector. With tanks in the assault role, the 34th Division infantry cleared the obstacle, allowing Bradley to send the 1st Armored Division through to victory. American troops entered Bizerte on 7 May and two days later more than 40,000 German troops surrendered to II Corps. The fighting in North Africa was over, and the U.S. Army, as Brad put it, had "learned to crawl, to walk - then run." He then went to Algiers to help plan the invasion of Sicily, the next objective in the Allied timetable approved at the Casablanca Conference. Capturing Sicily would, the Allied leaders hoped, knock Italy out of the war and clear the central Mediterranean of Axis forces. It might also divert German forces from the Eastern Front, partially satisfying Josef Stalin's ongoing demands that the western Allies open a second front against the Germans. Under command of George Patton's Seventh Army, Lieutenant General Bradley's II Corps was in the vanguard of the Operation HUSKY assault, and it moved inland against negligible resistance. The Germans and Italians were not surprised by the landings, however, and the hard fighting that began the second day characterized the remainder of the 38-day campaign. By 16 August 1943, British and American forces held Sicily. The conquest of Sicily ultimately persuaded Italy to withdraw from the war, but the Allied operation was less than a complete success. Advancing from the south of Sicily along two axes of approach in a classic pincer converging on the port of Messina, the Allies allowed the German units to escape across the narrow straits to the Italian mainland. Bickering between American and British commanders also continued. On the positive side, American troops had learned a lot more about fighting. They had conducted their first opposed amphibious landings and airborne assaults, brought four new divisions successfully into battle, and taken a field army into war for the first time. It was during the fighting in Sicily that war correspondent Ernie Pyle discovered Bradley and established his reputation as the "soldier's general." Whatever its defects, the battle for Sicily was an important step in preparing Bradley for his next job. Shortly after the fighting ended, Eisenhower told him that he would command an army and then activate an army group in the forthcoming landings in France. Brad traveled to the U. S. to select the staff for his new command, the First U.S. Army, stationed at Governor's Island, NY. The headquarters deployed to London, England in October 1943, and Bradley took on the dual task of First Army commander and acting commander of the skeletal 1st U.S. Army Group (subsequently re-designated the 12th Army Group). Eisenhower, appointed as Supreme Allied Commander for the invasion of Europe, arrived in England in January 1944. A short time later he confirmed that Brad would command the American Army Group when it was activated. But until the landings were secure, all American ground forces in northern France would temporarily be under the command of British General Sir Bernard L. Montgomery, who also commanded the Canadian ground contingent. For Operation OVERLORD, the assault on the Normandy beaches, the First Army was assigned three corps. The V Corps was commanded by Leonard T. Gerow, whom Bradley had known since his advanced course days at Fort Benning, and VII Corps was led by J. Lawton Collins, a division commander who had proved himself in the Pacific and a man whom Bradley had known during his teaching tour at Benning. The XIX Corps, under command of Charles H. Corlett, would follow the other corps ashore to establish the beachhead. Almost alone among the senior Allied commanders, Bradley believed in the value of airborne landings both to limit enemy access to the coast from inland and to spread confusion in the German defenses. He therefore fought to have the 82d and 101st Airborne Divisions dropped behind UTAH Beach on D-Day. During the months before the invasion, Bradley supervised the refinement of assault plans and troop training. He and his corps commanders finally decided that the assaults would be led by the 29th Infantry Division and elements of the experienced 1st Infantry Division on OMAHA Beach, and by the 4th Infantry Division on UTAH. Both assault forces would be supported by the new duplex drive M4 tank; a Sherman tank fitted with flotation skirts and propellers, which could be launched from landing craft and swim ashore. Brad decided American units would not use other specialized tanks, including the "flail" tanks that cleared minefields and tanks with flamethrowers, because they required specialized training and an extensive separate supply and maintenance organization. (Some have contended that this decision to keep a lean supply system cost the lives of many soldiers who died from mines and booby traps on the Normandy beaches and during the subsequent breakout.) On the morning of 6 June 1944, Brad was aboard the cruiser USS Augusta, his headquarters for the invasion. He received word that the Germans had moved the 352d Infantry Division into the area for training, an unfortunate event that increased the odds against V Corps. Still, he did not change his battle plans. At 0630 American troops and their Allies assaulted the Normandy beaches. Meeting only light resistance, the 4th Infantry Division suffered very few casualties and quickly secured UTAH Beach; VII Corps pushed six miles inland by the end of D-Day. The situation was a nightmare on OMAHA Beach. The German regiment there, reinforced by troops from the division that had unexpectedly arrived, occupied favorable terrain for defense and put up a stiff resistance. Landing craft launched most of the amphibious tanks too far out from the shore, where most foundered and sank. The aerial bombardment was almost completely ineffective in suppressing German defenses, and many of the assault troops were put ashore at the wrong places. For several hours the situation appeared to be a disaster in the making. Casualties were heavy, particularly among the demolition engineers assigned to clear the beach obstacles for following assault waves. The infantry, pinned down on the tide line, was also hit hard. In the end, good leadership and naval gunfire resolved the situation. Determined and courageous American commanders led their men in desperate local fights against the German position and slowly established a foothold. U.S. Navy destroyers, ignoring the hazards, navigated close inshore and fired directly into German strongpoints. When Gerow finally established communications with Bradley, his first message was "Thank God for the U.S. Navy!" Handicapped by scanty communications with the troops ashore, Brad quietly worried over what appeared to be a developing catastrophe. For a time he considered evacuating the troops and sending follow-on assaults to UTAH or the British beaches. At last, in the early afternoon, Gerow reported that his men were beginning to reach the bluffs above the beach. By evening the crisis was past, and V Corps had 35,000 soldiers ashore on a beach five and a half miles long and a mile and a half across at its widest point. At a cost of around 2,500 casualties, the Allies had established themselves firmly on the Normandy coast. On 9 June, Bradley moved First Army headquarters ashore. British and American forces repelled German counterattacks against the beachhead throughout the first half of June, including an assault by the 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division designed to penetrate the junction between the U.S. V and VII Corps. Using information code-named ULTRA (from the Ultra Secret classification assigned to the sophisticated code-breaking process), Bradley shifted the newly arrived 2d Armored Division to crush the German attack. Meanwhile, follow-on forces were steadily landing on the invasion beaches, and the Allied lodgment became secure. Over the next month Bradley sent VII Corps to capture the port of Cherbourg and expanded the beachhead into the hedgerow country behind the coast, preparing for the breakout envisioned in the OVERLORD plans. The first attempts at breaking out of the lodgment failed due to heavy German opposition. Bradley then conceived a plan for a one-corps attack centering on St. Lo, using heavy air support. The operation, dubbed COBRA, began on 25 July with a saturation bombing attack that fell on both American and German positions. Collins' VII Corps nonetheless assaulted on schedule. After pushing through the German lines, he committed two armored divisions to exploit the breakthrough. On Collins' right flank, Troy Middleton, commanding VIII Corps, likewise released an armored division after his infantry broke through the initial German resistance. In a 35-mile advance, the American armor reached Avranches and began a rout of the Germans that lasted just over a month, by which time the Allies had closed on the German frontier. With the breakout, Eisenhower activated Third U.S. Army with George Patton in command. Bradley turned First Army over to Courtney Hodges and activated 12th Army Group, which on August 1st assumed command of 21 divisions comprising some 903,000 men. No officer in the U.S. Army had any practical experience with the operations of an army group - few had even served in a division before World War II. Bradley finally decided to model his command technique on that of Sir Harold R. L. G. Alexander, the British general with whom he had served in the Mediterranean. Instead of providing only broad operational direction, as the vague prewar American doctrine foresaw for army group commanders, Brad planned to exercise close control of his armies. He decided to assign broad missions to his principal subordinates and then carefully monitor operations, intervening on a selective basis when he thought necessary. The first chance to test his plan came the week after 12th Army Group was activated. In what Bradley considered one of the worst mistakes anyone made in World War II, Adolf Hitler ordered his commanders to seek a decision in Normandy. Rather than withdraw, the Germans reinforced their units. Alerted by short-notice ULTRA information, Bradley reinforced the VII Corps sector at Mortain, where the German attack (Operation Lüttich) seemed aimed. The 30th Infantry Division, supported by tactical air power, decimated the assaulting force. (Several hundred Americans were killed by the bombings, including a senior general, and the use of heavy bombers to support infantry operations was not repeated.) Bradley, seeing the potential for a bigger success, devised a plan to trap the bulk of the retreating German forces west of the Rhine; a long encirclement that he envisioned as a war-winning maneuver. Unfortunately, the American and Canadian armies did not meet at the Falaise Gap in time to trap all the Germans and about 240,000 German troops escaped to fight again, although they left almost all of their heavy equipment. The Canadian forces were part of British General Sir Bernard L. Montgomery's 21st Army Group. Bradley and Eisenhower blamed Montgomery for moving the Canadians too slowly and for using green Canadian troops instead of his veterans. Still, the battle marked the end of the fighting in Normandy, where Allied forces had literally destroyed two German armies and pushed the enemy back into Germany. In practical terms, the battle determined the future course of the war. Hard fighting in Normandy, followed by the pursuit across France through the end of September 1944, wounded or killed more than 500,000 Germans and destroyed many divisions. For example, the famous 12th SS Panzer Division (Hitlerjugend; Hitler Youth) literally dissolved as a fighting formation. Taken together, Normandy, the Falaise pocket, and the retreat across the Seine, reduced the German Army to an infantry force with limited tactical mobility. German equipment losses were staggering: some 15,000 vehicles were destroyed or abandoned and, out of more than 1,000 tanks and assault guns committed to battle in Normandy, fewer than 120 were still operational in September. Few panzer divisions could muster more than a dozen tanks. The Allied armies were quick to exploit German weaknesses, closing to the borders of Germany by the fall. Assigning Hodges and Patton the mission of pursuing the retreating enemy, Bradley gave both commanders wide latitude of action and turned his attention to the growing problem of supplying forces that daily moved farther away from the invasion beaches. But neither he nor Eisenhower could significantly improve the logistical situation until the Allies captured usable ports. By September, the 12th Army Group was running out of supplies and encountering stronger German resistance along the Siegfried Line. With priority given to operation MARKET-GARDEN (an attempt to capture Arnhem and a bridge over the Rhine River) large-scale American movement basically halted and First and Third Armies continued only limited offensives. Bradley bitterly protested about the priority of supplies given to Montgomery, but Eisenhower, mindful of British public opinion, held Brad's protests in check. Bradley's Army Group now covered a very wide front in hilly country, from the Netherlands to Lorraine and, despite his being the largest Allied army group, there were problems in operating a successful broad-front offensive in difficult country with a skilled enemy that was regaining its balance. Courtney Hodges' 1st Army encountered difficulties in the Aachen Gap, and the Battle of Hürtgen Forest cost 24,000 casualties. Further south, Patton's 3rd Army lost momentum as German resistance stiffened around Metz's extensive defenses. While Bradley focused on these two campaigns, the Germans had assembled troops and materiel for a surprise offensive. On 16 December 1944, the Germans attacked in the Ardennes, an area that Bradley had left thinly garrisoned as a calculated risk. Brad's command would now take the initial brunt of what would become the Battle of the Bulge. (Over Bradley's protests, for logistical reasons, the 1st Army was once again placed under the temporary command of Field Marshal Montgomery's 21st Army Group. In his 2003 biography of Eisenhower, Carlo d'Este implies that Bradley's subsequent promotion to full general was to compensate him for the way in which he had been sidelined during the Battle of the Bulge.) Eisenhower quickly decided to convert the attack into an opening to break the back of the German Army. Agreeing with Eisenhower's assessment, Bradley, reorganized his forces to meet the threat and exploit the situation. He directed Patton to reorient his attack to the north, with the aim of relieving American forces besieged in Belgium. In what was probably his most impressive performance, Patton marched his divisions almost one hundred miles in bad weather in two days to attack the German left flank and link up with the 101st Airborne Division at Bastogne. Meanwhile, First and Ninth Armies fought tenaciously to contain the German attack, turning the Ardennes offensive into an unmitigated catastrophe for the German Army. (Clearing weather allowed air superiority to relieve Bastogne and break the German offensive.) Although the German losses in the fighting were not much higher than American losses, the battle cost the Germans the bulk of their skilled troops; eradicated their operational reserve; and destroyed great quantities of modern equipment. The Battle of the Bulge made the great victories of 1945 possible because it eliminated the German Army's ability to stop the final offensives into its homeland. In January 1945, having defeated the German winter attacks, Bradley began a series of continuous offensives that smashed through the Siegfried Line, crossed the Rhine, crushed the remains of the German forces in the Ruhr, and finally met the Soviets on the Elbe River. Since September 1944, and even earlier, the Allied commanders had debated the best way to end the war militarily. Eisenhower, in consultation with Bradley and Montgomery well before D-Day, had stipulated that the main Allied objective in Germany was the Ruhr valley, Germany's industrial heartland. A threat to that critical area would oblige the Germans to commit their remaining ground forces for its defense. In general terms, Eisenhower and his senior commanders envisioned an encirclement of the Ruhr that would capture the German industrial base and the bulk of the German Army at the same time, thus bringing the war to a close. The means of doing this remained controversial. Montgomery favored a single "knife-like thrust" from the north, under his command, to which all Allied resources would be committed. However, that concept, as embodied in Operation MARKET-GARDEN, proved unsuccessful. In contrast, Brad supported Eisenhower's determination to pursue a broad-front attack that was as important for domestic political reasons as for military ones. Once at the Rhine, chance presented him with the opportunity for improvisation. The retreating Germans had methodically destroyed Rhine River bridges to strengthen the defensive value of their natural barrier. The 9th Armored Division, under the command of Brad's classmate John Leonard, captured intact the Ludendorff railway bridge at Remagen on 7 March. The structure had been rigged for demolition with explosives but, inexplicably, had not been destroyed in a timely manner. Informed of that stroke of luck, Brad ordered First Army commander Courtney Hodges to push as many forces as possible across to the east bank of the Rhine and secure the bridgehead. He then obtained Eisenhower's approval to put as many as five divisions into an attack. Brad now saw that it was possible to strike at the Ruhr from the south, up the valley from Frankfurt, instead of from the British sector in the north. By 16 March he had pushed two corps over to the east bank of the Rhine and kept them moving toward the main north-south autobahn. At the same time, he ordered Patton to seek a Rhine crossing in the vicinity of Oppenheim and then to drive north toward Giessen, where he was to link up with First Army. With little difficulty, Patton crossed the Rhine on 23 March and immediately began his attack to the north. By 28 March, First Army had driven from the Remagen bridgehead through the Lahn valley and beyond Giessen to Marburg, where its III Corps met XII Corps of Patton's Third Army. The stage was now set for the final campaign of the war in Europe. Bradley planned to swing his Ninth Army south and First Army north in a double envelopment that would encircle the Ruhr and meet in the vicinity of Kassel. Once that was accomplished, he intended to detail some units to mop up the Ruhr and then attack with Ninth, First, and Third Armies from Kassel toward Leipzig and Dresden, halting at the Elbe River where American forces were to meet the Soviets. The operation developed very much as Brad planned, with the pincers closing around the Ruhr on 1 April. By 12-13 April, American units had reached the Elbe River. Bradley's troops had captured in excess of 315,000 prisoners; more than had been taken at Stalingrad or in Tunisia. In a final offensive, Bradley sent Patton's Third Army to attack along the Danube into Bavaria, Austria, and Czechoslovakia, thereby cementing the Allied success. At the end of operations in Europe, Bradley's 12th Army Group was the largest ever commanded by an American general. It consisted of Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges' First; General George Patton's Third; Lt. Gen. William Simpson's Ninth; and Lt. Gen. Leonard Gerow's Fifteenth Armies. The force comprised 12 corps, 48 divisions, and 1.3 million men. From the time of the TORCH landings in North Africa through the end of the war, Bradley was indispensable to Eisenhower, who greatly valued his perennial calm, understated professionalism, and sound advice. Since 1943 he had been intimately involved in every crucial decision that determined the outcome of the war in Europe. The Supreme Commander saw Bradley as "the master tactician of our forces," and at the end of the war he predicted that Bradley would eventually be recognized as "America's foremost battle leader." Post-War Service Months before the end of the war in Europe, Bradley had asked General Marshall to keep him in mind for an eventual command in the Pacific. Once Germany capitulated, it became evident that General Douglas MacArthur did not require another army group commander for his planned assault on the Japanese home islands. Bradley was still in Germany when news of the Japanese surrender reached him. President Harry S. Truman, it turned out, had other plans for Brad. On 15 August 1945, he appointed him to direct the Veterans Administration (VA). Somewhat reluctantly, Brad accepted the job and began to modernize and restructure that antiquated organization to meet the challenges that it would soon face. Before the end of the war the VA was responsible for some 5 million veterans, with a few pensions still going to cases arising from the War of 1812. By 1946, almost 17 million veterans were on its rolls. Bradley completely rebuilt the organization on a regional basis and insisted on basing his decisions on the needs of the veteran, rather than on the political considerations that had so often governed in the past i.e. the location of VA hospitals. With the help of Eisenhower's theater surgeon, Maj. Gen. Paul R. Hawley, he completely overhauled a medical care system that Hawley had described as medieval. He also revised and extended the educational benefits of the G.I. Bill; arranged for jobs and job training programs for men whose only experience had been as members of the armed forces; established a program of loans for veterans; and administered a staggering growth in veterans insurance and disability pensions. Bradley was unable to achieve everything he had hoped to do in his two-year tenure, but in the assessment of the press, he transformed "the medical service of the Veterans Administration from a national scandal into a model establishment." On 7 February 1948, Bradley succeeded Eisenhower as Army Chief of Staff and became immersed in a series of problems arising from demobilization of the Army, reform of its General Staff organization, and the unification of the armed services. In the international crises which followed - notably the hardening of relations with the Soviets - Brad fought for both sufficient budgets and modernization investments to meet the requirements imposed by the Truman Doctrine and containment. The results were mixed. Congress rejected Army proposals for universal military training, and the idea of bringing the National Guard under direct Army control foundered on the shoals of political interest. Bradley did, however, gain presidential support to extend the Selective Service System, and in 1949 he managed to secure an increase in military pay that brought it into line with equivalent civilian pay scales for the first time since well before World War II. After eighteen months, Brad turned over the job of Army Chief of Staff to J. Lawton Collins to accept another appointment. On 16 August 1949, he became the first Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), and on 22 September 1950 the 81st Congress officially promoted him to General of the Army with five stars. He was the last officer in the American military to have that rank, and the only one since World War II. Bradley served two terms (four years) as JCS Chairman and the years were exceptionally difficult ones. Major disagreements between the Navy and the Air Force over roles and missions had begun while Bradley was Army Chief of Staff and continued into his tour as JCS Chairman. When debates over nuclear deterrence and the value of conventional forces further exacerbated service differences, Bradley played an important role as a mediator. Internationally, he was involved in the creation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the rearming of Western Europe. He became the first Chairman of the Military Committee of NATO on 5 October 1949, serving in that post through 1950 and remaining as the U.S. representative to the NATO Military Committee until August 1953. As Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Bradley was the Pentagon official in charge of the Korean War and, as such, a constant adviser to President Truman. He was the chief military policy maker during the Korean War, and supported Truman's original plan of rolling back Communism by conquering all of North Korea. When Chinese Communists invaded in late 1950 and drove back Americans in headlong retreat, Bradley agreed that rollback had to be dropped in favor of a containment of North Korea. Containment was adopted and continues in the 21st century. Bradley was instrumental in convincing Truman to fire the field commander, General Douglas MacArthur, who wanted to continue the rollback strategy after Washington dropped it. In testimony to Congress, Bradley strongly rebuked MacArthur for his support of the rollback strategy. Soon after Truman relieved MacArthur of command in April 1951, Bradley said in Congressional testimony, "Red China is not the powerful nation seeking to dominate the world. Frankly, in the opinion of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, this strategy would involve us in the wrong war, at the wrong place, at the wrong time, and with the wrong enemy." His memoir, A Soldier's Story, (ghostwritten by A.J. Liebling) was released in 1951. During his service, Bradley visited the White House over 300 times and was frequently featured on the cover of TIME magazine. On 15 August 1953, Bradley retired from active service. Post-Retirement Activities & Honors (Sequential) After his retirement from the Army, Bradley held a number of positions in business and was periodically consulted by both civilian and military leaders. Included among his business positions was service as the Chairman of the Board of the Bulova Watch Company from 1958 to 1973. Bradley also retained an active interest in the U.S. Army, spoke at its schools, and frequently visited units and met with soldiers of all ranks. As a horse racing fan, Bradley spent much of his leisure time at racetracks in California and often presented the winner's trophies. He also was a lifetime sports fan, especially of college football. (He was the 1948 Grand Marshal of the Tournament of Roses and attended several subsequent Rose Bowl games.) His black limousine with personalized California license plate "ONB" and a red plate with 5 gold stars, was frequently seen driving through Pasadena streets, with a police motorcycle escort, toward the Rose Bowl on New Year's Day. In later years, he was also seen at the Sun Bowl in El Paso, TX, and the Independence Bowl in Shreveport, LA. Bradley served as a member of President Lyndon Johnson's Wise Men, a high-level advisory group considering policy for the Vietnam War. Bradley was a hawk and recommended against withdrawal from Vietnam. In 1970, Bradley served as a consultant for the film Patton. The film, in which Bradley was portrayed by actor Karl Malden, is very much seen through Bradley's eyes. While admiring of Patton's aggression and will to victory, the film is also implicitly critical of Patton's egotism (particularly his alleged indifference to casualties during the Sicilian campaign) and love of war for its own sake. Bradley is shown being praised by a German intelligence officer for his lack of pretentiousness, "unusual in a general." On 10 January 1977, Bradley was presented with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Gerald Ford. One of Bradley's last public appearances was at the festivities surrounding the inauguration of President Ronald Reagan in January 1981. The U.S. Army's M2 Bradley Infantry Fighting Vehicle and M3 Bradley Cavalry Fighting Vehicle are named after General Bradley. Personal Information Mary Elizabeth Quayle, Bradley's first wife, grew up across the street from him in Moberly, MO. The pair attended Central Christian Church and they graduated from Moberly High School together in 1910. On 28 December 1916, Omar Nelson Bradley married Mary Elizabeth Quayle in Columbia, MO. Mary was born 25 July 1892. Two children were born to their marriage; the first, a stillborn boy, was born in Butte, MT, in 1918. The second was a daughter, Elizabeth, born 3 December 1923, at West Point, NY. On 1 December 1965, Mary Bradley died of leukemia in Washington, DC. Bradley married Esther Dora "Kitty" Buhler on 12 September 1966, in San Diego, CA. It was her third marriage; the first two ending in divorce. Kitty was a motion picture screenwriter and a playwright for television and movies. Brad first met her in Okinawa in 1950 when she was a freelance writer for UPI and interviewed him. She lived in Southern California, where she worked as a screenwriter for the television series "My Three Sons" and "The Untouchables." She also wrote the feature film "China Doll" which starred Victor Mature, and assisted General Bradley when he was the technical advisor on the Oscar-winning film "Patton." After Brad's death, Kitty initially lived in Century City, CA, before moving to Rancho Mirage in the late 1980s. She had no children. During her marriage to Brad, she was active in the National League of American Pen Women, the Omar Bradley Foundation, and was one of the eleven members of the American Battle Monuments Commission, to which President Reagan appointed her in 1981. Kitty and Brad were married until his death. Throughout his life, Bradley called Moberly his hometown and his favorite city in the world; Moberly called Bradley its favorite son. During the course of his life and career, he was a frequent visitor to Moberly. He was a member of the Moberly Rotary Club, played near-handicap golf regularly at the local course, and had a "Bradley pew" at Central Christian Church. Bradley spent his last years in Texas at a special residence on the grounds of the William Beaumont Army Medical Center, part of the complex which supports Fort Bliss. Death & Funeral General of the Army Omar Nelson Bradley died of cardiac arrhythmia on 8 April 1981, just minutes after receiving an award from the National Institute of Social Sciences in New York City. As the nation mourned the passing of this great and noble warrior with full military honors, he was laid to rest next to his first wife, Mary, in Arlington National Cemetery on 14 April 1981. His second wife, Esther Dora "Kitty" Bradley, was buried next to him after her death on 3 February 2004. According to retired Lt. Col. Charles Honeycutt, a former aide to the general, Kitty died at the Eisenhower Medical Center in Rancho Mirage. The cause of death was pneumonia. Posthumous Honors Bradley's posthumous autobiography, A General's Life: An Autobiography, was published in 1983. Bradley began the book but found writing difficult, so Clay Blair was brought in to help shape the autobiography. After Bradley's death, Blair continued the writing and made the unusual choice of using Bradley's first-person voice. The resulting book is highly readable, and based on extremely thorough research, including extensive interviews with all concerned, and Bradley's own papers. In this book he took the opportunity to attack Field Marshal Montgomery's 1945 claim that it was he who had won the Battle of the Bulge. On 5 May 2000, the United States Postal Service issued a series of Distinguished Soldiers stamps in which Bradley was honored. Bradley's hometown, Moberly, MO, is planning a library and museum in his honor. Two recent Bradley Leadership Symposia in Moberly honored his role as one of the American military's foremost teachers of young officers. On 12 February 2010, the U.S. House of Representatives, the Missouri Senate, the Missouri House, the County of Randolph and the City of Moberly all recognized Bradley's birthday as General Omar Nelson Bradley Day. The ceremony marking the day was held at his high school alma mater and featured addresses by the current Congressional representative, and the Moberly High School Principal. Final Remarks From a rustic log cabin on a small farm in Missouri came a man who would become known as one of the greatest military leaders that has ever served our nation: Omar Nelson Bradley. A quiet but distinguished member of a notable class (1915) of West Point graduates, Bradley was the epitome of a remarkable generation of Army officers. Yet, at the end of World War I, he considered himself a professional failure because he had spent the war in the United States while his contemporaries had distinguished themselves on the battlefields of France. Despite this, he diligently carried out his duties through some of the Army's most difficult years. The fact that World War II coincided with Bradley's own professional maturity led to his promotion as the first general officer in his class. Army Chief of Staff George Marshall's confidence in Bradley assured him an opportunity to show his mettle. His gloomy self-assessment in 1918 was certainly premature. Thirty-five years later, Bradley had been the Army's Chief of Staff, and had served two terms as the first Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He also held the highest rank in the U.S. Army: The five stars of a General of the Army. He was the last officer in the American military to have that rank, and the only one since World War II. He had also more than made up for his lack of combat duty, for during World War II he successively commanded a division, a corps, an army, and finally a group of armies. His last command, the 12th U.S. Army Group, was the largest body of American soldiers ever to serve under one field commander; at its peak it consisted of four field armies and 1.3 million men. Except for his original division assignments, Bradley won his wartime advancement on the battlefield, commanding American soldiers in North Africa, Sicily, on the Normandy beaches, and into Germany itself. His understated personal style of command left newsmen with little to write about, especially when they compared him to the more flamboyant among the Allied commanders. But his reputation as a fighter was secure among his peers and particularly with General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander who considered him indispensable. From the time of the TORCH landings in North Africa through the end of the war, Eisenhower greatly valued his perennial calm, understated professionalism, and sound advice. Since 1943 he had been intimately involved in every crucial decision that determined the outcome of the war in Europe. The Supreme Commander saw Bradley as "the master tactician of our forces," and at the end of the war he predicted that Bradley would eventually be recognized as "America's foremost battle leader." Those remarks are especially meaningful since they were made by a classmate and a fellow General of the Army. As an Army Group Commander, there is no standard against which to compare Bradley. During the fighting in Europe, his calm and effective presence was important in times of crisis, as was his deft touch in handling subordinates. Will Lang Jr. of Life magazine said, "The thing I most admire about Omar Bradley is his gentleness. He was never known to issue an order to anybody of any rank without saying 'Please' first." It is difficult, for example, to imagine Patton without Bradley, who exploited the talents of that talented, yet volatile, commander as well as any man could have done. Finally, it was his superb wartime record, combined with his reputation for fairness and honesty, which made him so effective in what was probably his most difficult job; Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Self-effacing and quiet, Bradley showed a concern for the men he led that gave him the reputation as the "soldier's general" and the "GI's general." That concern made him the ideal choice in 1945 to reinvigorate the Veterans Administration and prepare it to meet the needs of millions of demobilized servicemen. After he left active duty, both political and military leaders continued to seek Bradley's advice. Perhaps more importantly, he remained in close touch with the Army and served its succeeding generations as the ideal model of a professional soldier. "Leadership is intangible, and therefore no weapon ever designed can replace it." General of the Army Omar Nelson Bradley |

||||

| Honoree ID: 12 | Created by: MHOH | |||

Ribbons

Medals

Badges

Honoree Photos

|  |  |

|  |

|